Artificial

Intelligence 3E

foundations of computational agents

4.2 Solving CSPs by Searching

A finite CSP could be solved by exhaustively searching the total assignments.

The generate-and-test algorithm to find one solution is as follows: check each total assignment in turn; if an assignment is found that satisfies all of the constraints, return that assignment. A generate-and-test algorithm to find all solutions is the same except, instead of returning the first solution found, it enumerates the solutions.

Example 4.10.

In Example 4.9, the assignment space is

In this case there are different assignments to be tested. If there were fifteen variables instead of five, there would be , which is about a billion, assignments to test. This method could not work for thirty variables.

If there are variables, each with domain size , there are total assignments. If there are constraints, the total number of constraints tested is . As becomes large, this becomes intractable very quickly.

The generate-and-test algorithm assigns values to all variables before checking the constraints. Because individual constraints only involve a subset of the variables, some constraints can be tested before all of the variables have been assigned values. If a partial assignment violates a constraint, any total assignment that extends the partial assignment will also violate the constraint. This can potentially prune a large part of the search space.

Example 4.11.

In the delivery scheduling problem of Example 4.9, the assignment violates the constraint regardless of the values of the other variables. If the variables and are assigned values first, this violation can be discovered before any values are assigned to , , or , thus saving a large amount of work.

Figure 4.1 gives a depth-first search-based algorithm to find all solutions for a CSP defined by variables and constraints that extend , a partial or total assignment. contains the variables not assigned in , and contains the constraints that involve at least one variable in . It is called initially using

where is the set of all variables, and is the set of all constraints in a CSP, with implicit.

It first collects in the assignments that can be evaluated given the context. If the context violates a constraint that can be evaluated, there are no solutions that extend this context. If there are no variables in , all variables have been assigned and so all constraints have been satisfied and it has found a solution. Otherwise, it selects a variable not assigned in the context and branches on all values of that variable.

This algorithm can be modified to implement generate and test by making it check the constraints only when all variables have been assigned.

The search-based algorithm carries out a depth-first search. It is possible to use any of the search strategies of the previous chapter to search the graph of assignments. However, as all of the solution paths are the same length – the length is the number of variables – there is not much point in doing so.

Example 4.12.

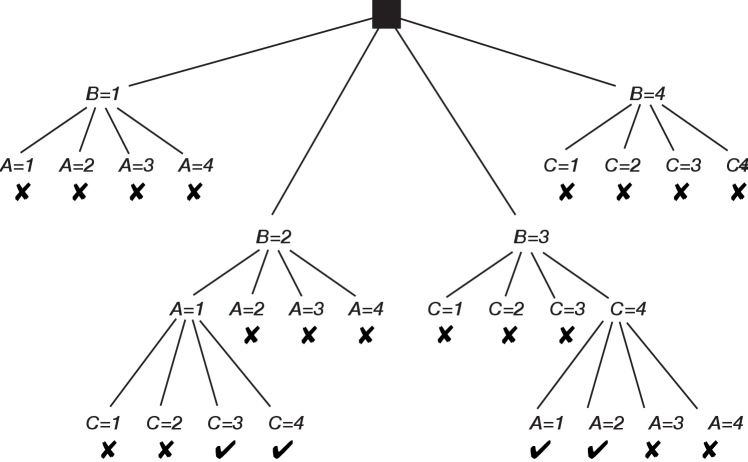

Consider a CSP with variables , , and , each with domain , and constraints and . A possible search tree is shown in Figure 4.2.

In this figure, a node corresponds to all of the assignments from the root to that node. The potential nodes that are pruned because they violate constraints are labeled ✘.

The leftmost ✘ corresponds to the assignment , . This violates the constraint, and so it is pruned.

This CSP has four solutions. The leftmost one is , , . The size of the search tree, and thus the efficiency of the algorithm, depends on which variable is selected at each time. A static ordering, such as always splitting on then then , is usually less efficient than the dynamic ordering used here, but it might be more difficult to find the best dynamic ordering than to find the best static ordering. The set of answers is the same regardless of the variable ordering.

There would be total assignments tested in a generate-and-test algorithm. For the search method, there are 8 total assignments generated, and 16 other partial assignments that were tested as to whether they satisfy some of the constraints.